After The Flood

1999 - 2014

The Sunday Times: 24th January 1999

Channel 4's new satire Boyz Unlimited presents a worrying picture of how boy bands are squeezing out grown-up music, says Andrew Smith.

Comedy writer Richard Osman decided that he wanted Boyz Unlimited, his six-part satire on the crazy world of boy bands, which begins on Channel 4 next Friday, to be played straight. After all, this was not an area that needed to be camped up. It was camp as a scoutmaster's tent peg already. The songs would thus be chosen for his hopeful quartet as if they were a real group - except for one, which, for the purposes of the plot, he wanted to be a mind-blowingly inappropriate cover version. He racked his pop-saturated brain, without finding anything quite horrid enough, until one day his joint musical director Ian Curnow called out of the blue with the answer.

The solution was to be found in Dr Hook, the insipid 1970s groaners whose baffling trademark was their singer's eyepatch and beard, and who are best known for the famously execrable When You're In Love With a Beautiful Woman. That was a bad song, but not their worst. Hook had another called A Little Bit More, a schmaltzy ballad that would make even Celine Dion cringe, and a very real contender for the title of Worst Song Ever, Ever . "It was perfect," Osman enthuses, sitting in a nondescript meeting room at the Soho headquarters of production company Hat Trick. "I thought, hell, this would be an awful thing to release - let's do it." So they did, and Osman was mighty pleased with the result. Until Curnow called again a few weeks ago to inform him that 911, a real boy band, were releasing their own reading of the same song and that it was likely to be at the top of the charts the following Sunday. To make matters worse, Osman contends that the fictional Boyz Unlimited's version is better. Reality: don't trust it, kids.

Interestingly, Boyz Unlimited is the second satire on the music business to appear on our screens in recent months. The other was Brian Elsley's racy The Young Person's Guide To Becoming a Rock Star, and the view it afforded of the business was remarkably of a piece with Osman's. Managers are clueless thugs, record companies staffed by cocaine-addled airheads. The would-be stars are likably deluded ingenues who are quickly denuded of all illusion and/or principles in the rush to fame and fortune. It's a funny picture, though not necessarily a pretty one, and for most of those entering the fray, it is reasonably accurate.

At 27, Osman has first-hand, or at least close second-hand, experience, because his brother is Mat Osman, the bass player in Suede. Although he claims not to have drawn directly on their career, he will allow that being around them has given him an insight into the way the industry works.

"It's different with them because they don't really play the game," he says, "but it has helped me to see the arbitrariness of it all. I mean, poor old Brett Anderson (Suede's singer), he's got this public image of being this foppish middle-class ponce, when all he is is this working-class boy who's worked his arse off and happens to be able to write brilliant pop songs. He's put through the wringer, when Damon Albarn, who is a foppish, middle-class ponce, is accepted as hard-working man of the people. There are many lessons learnt from the way Suede have been treated in my armoury."

Boyz Unlimited is acute and enjoyable, and far more barbed than Osman likes to admit. Some of us will be selfishly hoping that it serves another purpose, too. When the writer had approached Hat Trick and Channel 4 with his idea in 1997, their only concern was that, by the time it could be transmitted, the fad for teen pop would have passed. Osman assured them that it wouldn't have, and he was more right than he could have dreamt. The recently released list of last year's best-selling albums contains shockingly little original rock or electronic music. It is the blandest list of records anyone could have seen for at least 10 years, populated almost exclusively by the likes of the Corrs, Boyzone, Celine Dion, Steps, Savage Garden, B*Witched, 5ive and Billie. At the same time, someone must have been cloning boy bands. This year, you can't turn a corner without bumping into Another Level, E17, Bad Boys Inc, Ultra, 911, Backstreet Boys or Westside.

This appears harmless enough, until you look more closely. Let's start by noting that most of this stuff is abominable. The fascination with throwaway pop has always been that some of it mysteriously transcends its origins and lasts. The Beatles, Monkees, Motown, Wham!, and Stock, Aitken and Waterman all began with music that was considered disposable. The difference between then and now is that those songs were being written by the likes of Lennon and McCartney, Neil Diamond, Carole King and Gerry Goffin, Norman Whitfield and George Michael. They were forging the formulas that the faceless songwriting teams who provide hits for bands such as Boyzone and the Backstreet Boys at best ape, at worst parody. There is more to life than treacly ballads and damped-down disco. But not if you're a boy band.

De Gelderlander: 19th February 1999

Zwijmel Zwijmel had deze Britse bombast-band uit de eighties beter kunnen heten. Een hit als It's my life was altijd koren op de molen van de super-weemoedige geesten onder ons. Toch had Talk Talk meer kwaliteit in huis dan tien jongens-bands bij elkaar. Zanger en componist Mark Hollis wist als geen ander emotie zeer gecontroleerd in tekst en muziek samen te ballen. De beste nummers van Talk Talk waren knap geconstrueerde hoogstandjes, die net aan de goede kant van de kitsch bleven. Live moet zoiets bijna wel tegenvallen. Niet altijd even goed bij stem, met een band die teveel ruimte neemt, laat Hollis op deze concertregistratie horen waar het mis gegaan is. Such a shame. HW

^ go back to topDe Gelderlander: 19th February 1999

Swoon Swoon would have been a better name for this bombastic British band form the eighties. Hits such as It's My Life were always grist to the mill of the super-wistful spirits among us. Nevertheless, Talk Talk had more home-grown qualities than ten boys-bands put together. Singer and composer Mark Hollis knew how to control emotion in words and music like no other. The best songs of Talk Talk were handsomely constructed delights, which stayed just on the right side of kitsch. Live performances must therefore be something of a disappointment. Not always in good voice, with a band that takes up too much space, on this recording of Hollis you can hear where it went wrong. Such a shame.

^ go back to topThe Times: 6th March 1999

Despite the recent Eighties revival, it's still fashionable to view the music of Thatcher's decade with blanket disdain. It's a shame, because among the flimsy pop there were true mavericks who have never found a home in the renegade Nineties. Singer Mark Hollis guided Talk Talk from new romanticism to jazz-rock experimentalism and this, a record of their last live show, finds them at the half-way house. There's a taste of what's ahead in the exquisite piano prelude to Tomorrow Started, and in the extrapolation of Does Caroline Know? to a languid seven minutes. But listen to the close of Living in Another World and the deceptively simple Life's What You Make It and realise that only a band who had mastered the pop/rock idiom could retreat from it so magnificently.

(9/10)

^ go back to topThe Sunday Times: 30th October 1999

After the success of 1986's The Colour of Spring, Talk Talk, leby Mark Hollis and Tim Friese-Greene, retreated to an abandoned church for 14 months and bizarrely, resurfaced as an ambient jazz ensemble.

The result of truely audacious, at various points recalling the modern classicism of Debussy, musique concrete of Eric Satie and gentle whispereing of Brian Eno. Their record Comapny, EMI, were horrified, byt time has vindicated the transformation.

^ go back to top

The Times: 4th March 2000

Wherever people rail against the incompetence of the corporate music industry or catalogue the injustices meted out to bands of quality, it is quite likely that Talk Talk will be used as a cautionary tale. In the first stage of their career, EMI took one look at their synthesizers and the choppy pop of their eponymous early single and dressed this elegant, literate band in white silken box-jackets to fill the support slot on the road with Duran Duran.

Later successes with It's My Life and Life's What You Make It forced them into the wildly inappropriate role of hit factory, and by the time they released their fourth album, the jazz-inflected pop experimentation of Spirit of Eden in 1988, singer Mark Hollis and songwriting partner Tim Friese-Greene were refusing to let executives have either advance tapes or singles. Needless to say, amid a legal storm, Talk Talk were dropped, and turned to Polydor to put out their final album Laughing Stock.

Originally released in 1991, you can only imagine the label managers' despair when they discovered they had been handed 45 minutes and six tracks of freeform ambience. The album was deleted after three months.

Grandly speaking, then - and after exposure to this record's measured melancholy, everything seems grand - Laughing Stock is an album produced from artistic struggle, the work of men fighting to claim the peripheries of their pop remit. Untouched by contemporary trends - you will find no indie-dance, grunge or shoegazing here - Talk Talk were quite simply doing their own thing, following dark paths that will surprise anyone who remembers them merely for their brush with chart fame and the long-coated appearances on Saturday Superstore's Video Vote.

This reissue on Pondlife chimes unexpectedly with many recent developments in today's rock landscape. In the instrumental richness and exploratory dynamics it is not fanciful to see connections with the world of post-rock, from Ariel M's pastoral drifting to the oblique jazz interests of Tortoise. However, it is still very sad music, a sense of dislocation eloquently expressed by Hollis's fragile vocals and his lyrics of sin and redemption.

From the opening Myrrhman - a haze of strings and guitar - to the improvisatory squall and swell of After the Flood, it's clear that the singer's concerns stretch beyond mere love and into the spiritual realm. You could see it as the deconstruction of the relatively conventional hook-driven pop of Life's What You Make It. Tracks such as the sparsely dissonant Taphead, the soulful Ascension Day and New Grass, with its string flurries, rise slowly from a mist of instrumentation, but the emotional heat here stops Laughing Stock from being mere academic indulgence.

Most vitally though, this is music brimming with ideas, unafraid to turn from populism to musical libertarianism. Simon Le Bon might not have had too much to worry about, but the rest of us should feel humbled - and in certain cases, ashamed - that such music could slip through the net. (Victoria Segal)

(8/10)

go back to topUncut: April 2000

Talk Talk’s oblique yet blissful Laughing Stock represents a single-minded quest to achieve post-punk purity. By David Stubbs.

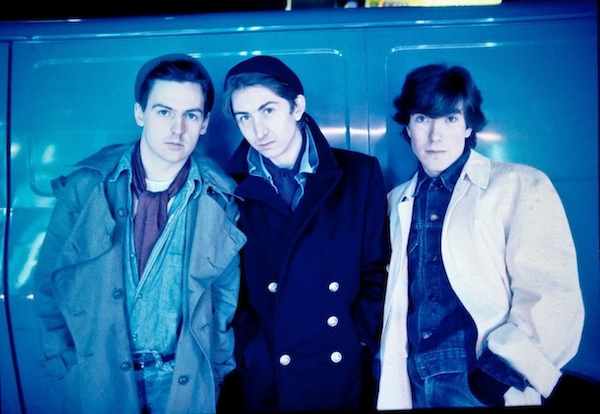

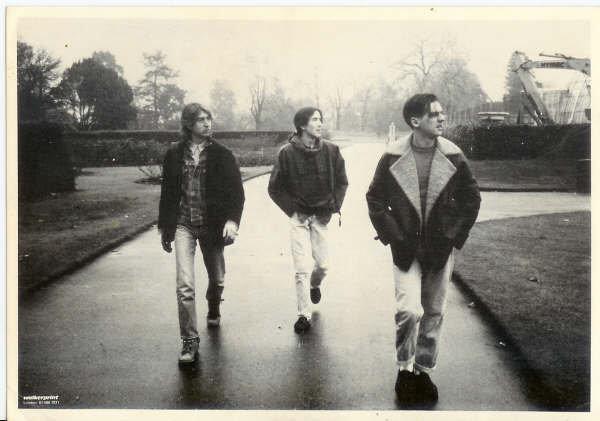

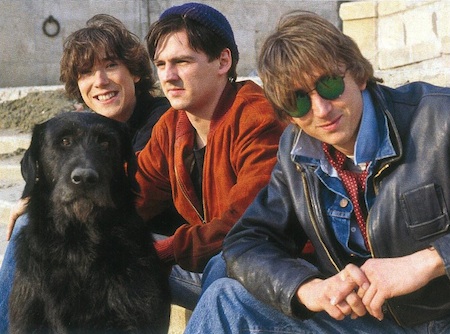

The musical journey undertaken by Talk Talk from centre-right pop to the far, far left of post-rock remains unique in music history. Mark Hollis started band life like anyone else in the late Seventies, in a post-punk combo known as The Reaction. His brother Ed was already in Eddie and The Hot Rods and when The Reaction disbanded in 1979 it looked like M. Hollis was destined to join the footnotes and also-rans of punk folklore.

When he hooked up with drummer Lee Harris and bassist Paul Webb, however, with a newer wave outfit by the name of Talk Talk and then caught the eye of esteemed arbiter of taste David ‘Kid’ Jensen, Hollis was back. EMI signed them up and divined in their smart, smooth poptones the ideal undercard to Duran Duran, then the leading lights of New Romantic. The release of an eponymous single, a shiny, synth-pop replication of the Duran sound, few imagined that this lot would be around for long, pre-destined to be Eighties, one-off curios a la Living In A Box.

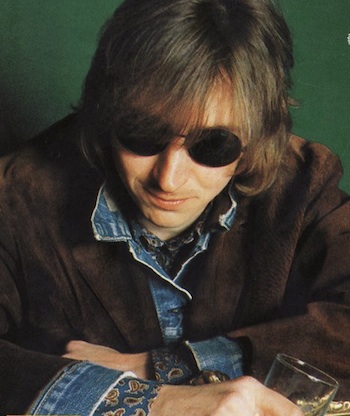

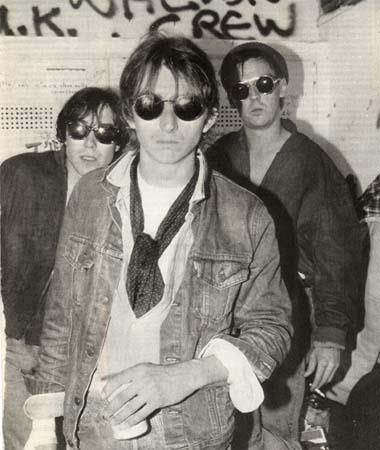

Yet few reckoned with Hollis’ revulsion with the trappings of pop and his undeflected search for a “purity” in the practice and making of music. This last quality would ensure that Talk Talk outlasted the Durannies, Toyahs, Kajagoogoos and similar flossy pop flunkies. By the mid-Eighties, they’d amassed a solid international following, outranking the likes of Spandau Ballet on European bills. This, in spite of Hollis’ insistence that no photos of the band appear on their cover sleeves, only illustrations, so as to disconnect “image” from the music. Moreover, producer Tim Friese-Greene had been drafted in as co-songwriter and keyboardist, whereupon Talk Talk’s sound took on the more sophisticated hue of the likes of Traffic or Roxy Music, stylish rather than fashionable, reflective rather than glossy.

By 1986, these qualities of endurance and integrity earnt them massive sales with that year’s The Colour Of Spring and the single, “Life’s What You Make It”. Yet Hollis was visibly disgruntled. He made no secret of his distaste for fans who only came to Talk Talk gigs to hear the hits, while a truculent NME interview, in which he insistently referred to his music as “art”, demonstrated his discomfiture with having to sell his wares in the pop market place.

The NME were unimpressed but EMI were downright perturbed. In reward for the high sales of The Colour Of Spring, they had lavished on Talk Talk a generous budget for their next release, only for the band to disappear from view for a couple of years. When they re-emerged, it turned out that they had done what every megapop band talks about doing but so rarely does – i.e. what they fuck they wanted. And this turned out to be 1988′s Spirit Of Eden was a staggering, critic-pleasing, commercially suicidal foray into the amorphous arms of ambient jazz-rock. Taking its cue from the melancholy spirituality of Miles Davis’ “He Loved Him Madly”, its aqueous, oceanic odysseys into oblique spiritual introspection (ouch! – Ed’s note) blew gaskets in executive boardrooms. EMI tried to salvage something from what they regarded as the wreckage, issuing an edited version of the gorgeous “I Believe In You” as a single, under protest from the band. However, the intricacy of Spirit Of Eden’s arrangements was such that Talk Talk declared they would be unable to promote the album on the road.

Relationships between the band and the label deteriorated, especially when EMI issued an album of remixes of old Talk Talk singles in 1990, which they had to withdraw after legal action from the band. By 1991 Talk Talk switched to Polydor, who allowed them to release an album, Laughing Stock, on their reactivated jazz label, Verve. It was oblique. It further confounded the expectations of traditional fans. It sold poorly. It was the last we would hear from Talk Talk as a collective – end of story. Oh and it was brilliant. If Spirit Of Eden represented the first tentative unmooring of a band looking to go further inward/further outward than any band had gone before, then Laughing Stock saw them way out to sea.

“Myrrhman”, the opener, sets the tone, rising slowly into being from a sort of meditative silence, back into which it continually threatens to evaporate. It drifts like a ghostship off the furthermost Northern coast, with flugelhorns pealing, subdued, through the fog of indistinction and a harmonium droning in a faint echo of Shetland folk music. The odd burst of radio crackle is suggestive of the last blast of modern electrical equipment, or communication with dry land, finally petering out. The strings offer a melancholy reminder of Gavin Bryars’s The Sinking Of The Titanic as Hollis & co gravitate towards an uncertain grey area where sea and sky merge.

Our bearings are a little surer on “Ascension Day” – we’re located somewhere beyond jazz, beyond rock, beyond folk. Hollis’ tremulous, plaintive vocals are somehow so intimate, the vowels so intense that it’s hard to make sense of them (still less his lyrics as reprinted in his semi-legible handwriting on the sleeve). “Bed I’ll be damned/Gets harder to sense, to sail . . .”. There is, however, a non-specific urgency, a Beckettian determination, stressed in the single, clanging, sustained guitar chord which concludes the song before being chopped off. Fade from grey once more with “After The Flood”, whose swelling, organ-driven pulse is a thing of simple but ominous beauty, with Hollis’ vocals rising off its surfaces like mist off water. Again, the mood of the song intensifies, refusing solace, naturally broken up by an agonised, distorted “guitar solo”, running like a scratch through the track, sounding like a morse distress signal obliterated in its own crackle.

“Taphead” sets out sparingly, with Hollis almost prayerfully murmuring, “Will to wind and wander/Climb through needle neck to consent . . .”, before a brace of shrill horns and harmonica blasts arise, all squealing and agitated, like whales aroused from their slumber and communicating anxiously with one another in song.

Perhaps the finest track on Laughing Stock, however, is the somehow optimistic “New Grass”. From its subdued, sublime jazz-rock beginnings, through to its concluding bars, in which it reincarnates from near, dead silence, replenished with new colour and rising joyously again, it’s late Talk Talk at their finest. This isn’t “jazz-rock” in any pyrotechnical sense but “uncomplicated”, ebb, flow, overlap and retreat, as simple yet profound as the sea.

Finally comes “Rune II”, skirting the edges of silence, observing to the end the sheer naturalness, the musical correctness of Talk Talk.

Of course, to those who were trying to flog the thing, it was just a bunch of exasperating, incomprehensible rock bollocks showing all the advanced symptoms of career death wish. As far as the bloody-minded Hollis was concerned, however, this was simply his own, unique extension of the three-chords-or-less punk ethic. He sat out most of the Nineties, perfecting the studio conditions to release his first, eponymous 1998 solo album, a further, magnificent retreat from the “centre”, an Aeolian instrumental interplay of wood, metal, wind and strings.

As for Laughing Stock, now at last available once more on CD, it may not be lyrically easily understood but that’s not the point. On a subliminal, emotional, musical level it’s one of the most cogent records ever made, blissful yet troubled, oblique yet desperate to connect. It offered a sonic template to a host of subsequent post-rockers, from Bark Psychosis to Spiritualized, to Labradford. It showed that there is a vastness of possibility out there to anyone who wants to do more than just flog their product. It’s renegade albums like Laughing Stock, slipping through the commercial nets, which end up making the whole sordid music business worthwhile.

^ go back to topTijd Nieuwslijn: 5th September 2001

Begin jaren tachtig liet Talk Talk voor het eerst van zich horen binnen de New Romantic-beweging. Dat was een androgyne modegril van een reeks bands die het doemdenken van de uitstervende punkbeweging een hak wilden zetten. De ingredienten zijn u waarschijnlijk nog bekend: een batterij synthesizers, veel make-up, gefoehnde haarlokken en een outfit waar ze vandaag nog beschaamd over zijn.

Talk Talk paste aanvankelijk perfect in het rijtje dat bands als Duran Duran of KajaGooGoo huisvestte en scoorde hoog op de hitladder met o.a. Talk Talk, Such A Shame of Its My Life. Met The Colour Of Spring - denk aan Lifes What You Make It - maakten voorman Mark Hollis en kompanen duidelijk dat er een ander tijdperk aangebroken was. Het geijkte popformaat ruimde plaats voor invloeden uit de minimalistische en klassiek-moderne muziek met heel wat ruimte voor jazzimprovisaties.

In 1992 verscheen op het jazzlabel Verve het uitmuntende Laughing Stock, een even bizarre als intrigerende geluidstrip met een hoog ambientgehalte. Het nieuwe Missing Pieces bestaat uit verschillende versies van tracks die tijdens de Laughing Stock-sessies waren opgenomen en wordt voor de fans aangevuld met twee voorheen onuitgegeven tracks, Stump en 5:09. Ook een zeer minimalistisch wat naar Satie neigend solopianostuk van Hollis moet de potentiele koper over de brug lokken. De compositie komt uit het album AV 1 dat in 1998 werd uitgegeven en een reeks audiovisuele installaties begeleidde van een zekere Dave Allinson. Missing Pieces laat zich bij momenten smaken als een indrukwekkend stukje soundscaping maar enkel doorgewinterde Talk Talk-liefhebbers zullen het van de eerste tot de laatste noot uitluisteren.

^ go back to topTijd Nieuwslijn: 5th September 2001

At the beginning of the 1980s Talk Talk debuted for the first time as part of the New Romantic movement. That was an androgynous fashion whim by a series of bands that wanted to put the boot into the doom-mongering of the dying punk movement. The ingredients you are probably familiar with: a battery of synthesizers, a lot of makeup, over-hairsprayed hair and outfits which they are probably embarrassed about today.

Talk Talk initially fitted in perfectly with bands like Duran Duran and Kajagogo and scored high in the charts with Talk Talk, Such A Shame and Its My Life. With the album The Colour Of Spring-think of Life’s What You Make It- leader Mark Hollis and accomplices made clear that a new era was dawning.

The calibrated pop format gave way to influences from the minimalist and modern classical music with a lot of room for jazz improvisations. In 1992 the excellent Laughing Stock appeared on the jazz label Verve, a both bizarre and intriguing sound trip with high ambient sound levels. The new Missing Pieces consists of different versions of tracks that were recorded during the Laughing Stock sessions -and supplemented with two previously unreleased tracks for fans, Stump and 5:09. Also included to lure potential buyers across the line is a very minimalist Satie-esq solo piece from Hollis. The composition comes from the album AV 1 that was issued in 1998 to accompany a series of audiovisual installations by a certain Dave Allinson. Missing Pieces can be at times feel like an impressive piece of soundscaping but only seasoned Talk Talk-enthusiasts will be listening from the first to the last note.

^ go back to topPopMatters: 10th September 2001

“Something awful has happened; something terrible. Something worse, even, than the fall of man. For in that greatest of all tragedies, we merely lost Paradise—and with it, everything that made life worth living. What has happened since is unthinkable: we’ve gotten used to it”. —John Eldredge, The Journey of Desire

Mark Hollis bears a striking resemblance to the mosaic visage of the Byzantine emperor Justinian in Ravenna, whose arched eyebrows and stern face were set upon establishing a new code of law. After three successive (and successful) forays in the realm of early ‘80s new romantic synth-pop, Hollis and Talk Talk producer Tim Friese-Greene entered a musical cocoon—an abandoned church building in England—to reinvent the band and explore brave, new sounds. When Spirit of Eden slid from its chrysalis in 1988 it took the collective breath away from critics worldwide, and drew down the ire of Talk Talk’s label. The highly non-commercial nature of the album resulted the band’s dismissal from EMI, a company whose artistic straight-jacket is more confining than the BBC’s. Notwithstanding, Talk Talk—yes, the same group who were once the airbrushed acolytes of Duran Duran—floated away with what is arguably one of greatest achievements in popular recorded music. Mark Hollis made an album for the ages and, unlike many of his classical predecessors, has lived to see it appreciated.

When most people enjoy a record, they generally speak of the music’s vibe. It makes them feel good for no specific reason; it provides a pleasurable escape from the agitations of life. But sample the reactions of those who have listened to Spirit of Eden, and it’s immediately apparent that this record draws out the most private emotions. On Amazon.com the listener reviews include the following observations:

“It’s the kind of music that makes you want to cry or write poetry”.

“It will cleanse you”.

“I don’t even need to play it anymore; it’s taken up permanent residence within”.

“. . . [it] caused me to ache, to sit still engrossed”.

“You can feel the surrender of a man”.

“If my house was on fire and I could save only one object, it would be this CD”.

“Take my freedom, for giving me this sacred album”.

“I played this album at my son’s birth”.

What’s going on here? Why would Spirit of Eden become a person’s most prized possession, an object that would be invited into the most intimate moments? It is one of those rare works that causes the listener to get in touch with the inner self—safely. It drags us by the ear to regions of the heart we would not voluntarily visit on our own. Spirit of Eden has been labeled prog, ambient, experimental; I prefer to see it as a soundtrack. As such, it suits those quiet moments when, deprived of all the devices and distractions we fill our lives with, we come precariously close to the sickening feelings of our ontological lightness. When life begins to lose its artificial meaning and contrived purpose, when we feel our complete aloneness and despair, when we realize something dear is lost, that’s when a record like Spirit of Eden speaks to the soul and says, “the fear is excruciating, but that is where your deliverance lies”.

Spirit of Eden was fueled by Hollis’ own life and death struggle. Having been addicted to heroin, he arrived at the conclusion that this prop, too, had to be kicked away. The terror of letting go of the one thing that gave a false sense of control inspired the cavernous sound of the record, and within those echoing canyons Hollis pushed through to resolution.

“Take my freedom, for giving me a sacred love”. (“Wealth”)

Ditching the taut tones of Casio keyboards, Talk Talk utilized a wholly organic sound for Spirit of Eden: real drums and real guitars augmented by harrowing improvisations on woodwinds and brass. Sustained, irregular piano chords announce thematic changes while swells from a church organ cause the record to draw deep, labored breaths. The falling and rising of the music, from thick silence to cacophony, is the main characteristic of this album. Techno? New romantic? MTV? Although this music has no direct antecedents, as a matter of reference it feels like Thelonious Monk, Dmitri Shostokovich, and Iron Butterfly meshed together. Yet, there is a timeless if not ancient character to the sounds that reaches across varied traditions. The tracks sprawl to an average length of nearly seven minutes. The lyrics are appropriately cryptic and non-specific. Spirit of Eden bypasses the head and sets a mood directly for the heart.

I was impressed by the fact that one amazon.com contributor played this album at his son’s birth. I recently had a very different but no less dramatic association with this music. About a month ago I received a phone call at work. My wife’s voice on the other end was gripped with terror and grief. Her brother had been in a serious fall, which fractured his skull. Shortly after being admitted to the hospital he went into cardiac arrest and had no heartbeat for about three minutes. The doctors feared the loss of oxygen had caused substantial brain damage. Within a few days his vital organs began to shut down, and the family was called in to expect the worst.

The day he was expected to die, the intensive care unit was filled with a procession of people, most of them young, most of whom I didn’t know, coming to tell this young man goodbye. While the sound of life support machines droned in the background, one by one these grieving people made their approach to his bedside, trembling, eyes and noses red, some of them clutching at their sides as if to hold themselves together. I remembered reading an Irish mystic, J.B. Stoney, who had said that there was nothing more dignified than the solitude of grief. Many were there, but each was alone with his or her own inexplicable feelings. As I watched, it struck me that the song “I Believe in You” was playing in my mind.

“On a street so young laying wasted

Enough ain’t it enough

Crippled world

I just can’t bring myself to see it starting….”

It was the song on Spirit of Eden that signified Hollis surrendering his control through addiction, allowing himself to fall into the hands of raging omnipotence. I thought it strange that, out of the hundreds of songs and hymns I know, this particular piece by a distant British rock band would rear up in my mind. But as the people around me quietly wept, I could hear the sound of Tim Friese-Greene’s church organ and the Chelmsford Boys Choir building inside.

“It’s taken up permanent residence within”.

Those voices resonating within me were like a comforting, heavenly choir. For a moment I had new eyes to see something most precious. These people were silently acknowledging that death is not what should have been, that no matter how we try to kill the desire, there is a demand for something eternal that only moments of loss such as this can stir. These were people jarred from the numbness of routine, becoming human again.

Spirit of Eden is a record that cuts to the marrow, challenging our resigned contentment with the way things are. It’s a spirit that slides under the gates of time and genre, reaching up to haunt us out of a stupor. Like any great art, it defies analysis and can only be experienced at the most individual level.

Heaven bless you, Mark Hollis.

^ go back to topThe Sunday Herald: 20th October 2000

What happens when the torch song chanteuse from Portishead teams up with a former Talk Talk member? They make beautiful music together, finds Graeme Virtue, as he tracks down Beth Gibbons and Rustin' Man

My first exposure to the sullen, sour strains of Portishead left an indelible mark on my memory. At the time - late August in 1994 - their single Sour Times really was unlike anything I'd ever heard before, certainly light-years away from the brewing Britpop scene. The musical backdrop - a blend of cinematic atmospherics, scratched beats and emotionless beeps - has since moved slowly from otherworldly to commonplace. But there's still something obdurately unique about the voice of Beth Gibbons - a raw, confessional frisson that can make the hairs on the back of your hands bristle.

But Portishead appear to be on an unending sabbatical - not a Theremin peep has been heard out of them since a shivery live album in 1998. The reclusive Gibbons, however, has re-emerged in a low-key collaboration with Rustin' Man - aka Paul Webb, founder member of 1980s art-rockers Talk Talk. Listening to the new material, it's almost like hearing Portishead for that first time again. Even in a musical landscape that stretches from the Technicolor choir-rock of The Polyphonic Spree to the crammed, sci-fi beats of modern R'n'B via the vinyl collage of DJ Shadow and The Avalanches, this is a record that still sounds like it's been recorded in some alternate folk-tale dimension: sparse, echoing and hypnotic, the songs linked by Gibbons's lacerating vocal delivery. It's a thing of uncommon beauty. But, according to Webb, we're lucky we're getting a chance to hear it at all.

NME: 15th November 2003

During the most difficult times at the back end of adolescence I clung to Talk Talk’s album ‘Laughing Stock’ like a life raft. It comforted me and was just a very, very important part of my life.

It’s perfect music to drop off to at night, or to spend b a window on a simmer’s day, or to have on your headphones on a long journey. You can escape into your own world with it. The dynamics, sensitivity and facility of it just makes it very fresh, organic and pretty tieless. I also like it because it’s very easy music to listen to on one level, yet there are so many tiny intricacies.

The first time I heard them was in 1985. My sister had one of their records and I remember it echoing from her bedroom into mine. I used to love it when it was on. I always used to open my bedroom door and make sure I caught it. It was kind of embarrassing that my big sister was influencing my taste – at the time anyway. NO chance would I have let her know she turned me on to anything.

When I was 21 my first love left me for a Venezuelan lawyer. So there’s me on the dole in Lancashire feeling really miserable. But I snapped out of it one Sunday afternoon. I put ‘New Grass’ (from Laughing Stock) on really loud and my housemate Alan wandered into my room, sat down, smoked some rollies and didn’t really talk.

I ran into him three months ago and we talked about music and Talk Talk and ‘New Grass’ in particular. I said ‘You were there when that track meant the most to me’ and he remembered: the same time and the same moment, so there must have been something in the air. Peter, our bassist, is under strict instructions to play ‘new Grass’ at my funeral if I go before he does! It’s beautiful, so delicate and fresh and very hypnotic. The name is perfect – it sounds like new growth, something blossoming, and no doubt some of my relatives could think it’s a drug reference!

It’s probably only their last three records that I like. They were marketed as a Duran Duran copy band and when they realised what was going on they withdrew into themselves. In the latter stuff there’s a jazz influence and blues in the guitar style. You can hear on certain tuned the sound of someone desperately looking for something. I don’t know what it was, but you’ve got to go somewhere to come back with that music. They’re the closest I’ve heard somebody come to hitting a pure, original angle. I bet they weren’t happy with it but I can’t fault any of it. They gave me something to aim at…which I’ll probably never achieve.

What to Buy:

It’s My Life: The transition, as they tentatively began to shed their Duran Duran wannabe mantle. The title track has been covered confidently by No Doubt.

Spirit of Eden: Dropping keyboards for minimal orchestration, Hollis was a perfectionist inspired by everything from ambient music to jazz Ambitious and stunning.

Laughing Stock: The final album and their greatest statement. Extraordinary hypnotic music that remains nothing less than crushingly beautiful throughout.

^ go back to topIndependent on Sunday: 4th January 2004

In the wake of No Doubt's cover of "It's My Life", EMI have wasted little time in inviting a reappraisal of Talk Talk, one of the lesser names of the New Romantic era. Twenty years ago, the label tried to market TT as another Duran Duran, but foghorn-voiced singer Mark Hollis didn't have the looks or the larynx for pop stardom (it has to be conceded, grudgingly, that "It's My Life" is improved by the replacement of Hollis' vocal with a female one, with the rider that one wishes it did not have to belong to Gwen Stefani). After two albums in a similar vein, TT finally found their own sound with 1986's The Colour of Spring, acknowledged as the band's masterpiece by anyone who was still listening. This randomly era- hopping compilation doesn't help the listener to follow their chronological progression, but hearing the elegant "Life's What You Make It" immediately after the sub-Spandau "Strike Up The Band" is a stark indicator of how far Talk Talk travelled.

^ go back to topBroadcast Music Inc: 19th October 2004

BMI songwriter/artist Mark Hollis (PRS), who was unable to attend this year’s London Awards stopped by the BMI London office to pick up a Pop Award for his song “It’s My Life.” Originally a hit for 80s synthpop band Talk Talk of which Hollis is a member, the 2003 No Doubt remake is still enjoying international success.

^ go back to topPortland Mercury: 4th March 2004

It's gotta be hard to shoot for the sublime. Mark Hollis has been doing so since 1981, ever since Island Music helped him book demo sessions with his industry-connected brother. From that moment on, Hollis' recordings have documented his inspirational, sometimes-obsessive passion for recorded sound. By Joan Hiller

I remember the first time I heard Talk Talk's Spirit of Eden--a friend of mine, flabbergasted and appalled that I'd never spent time with Hollis' records, gave me his copy--to keep. He said I'd need it. I'd been having a shitty year--bad decisions permeated by worse consequences, overworking myself, overextending myself, lending too much energy to the tending of other people's circumstances that were beyond my control--and I took it. Went home. Roommates were asleep. I grabbed my headphones (the big, shitty, old headphones that used to belong to my dad; the same headphones that filtered Steely Dan's Can't Buy a Thrill and Linda Ronstadt's Greatest Hits II into my prepubescent ears years ago), kept the lights off, and sprawled out spread eagle on the hardwood floor. The opening movement of "The Rainbow" trickled in, and I cried.

Noting, of course, that definitions of perfection are abstractly objective, few disagree that Spirit of Eden is anything less than exactly that. Hollis' climb towards Eden and beyond, of course, wasn't a short or easy one. After Talk Talk signed to EMI and released their debut, The Party's Over, in 1982, it was apparent to both critics and contemporaries that the label was using the group to ride the New Romantics wave straight to Hitsville. EMI was rakin' it in with the similarly double-monikered Duran Duran; and Talk Talk's first two bubbly yet sexy, broody synth-pop singles ("Mirror Man" and "Talk Talk") flopped like the rip-offs they were, while the punchier "Today" charted well. Hollis, happy with the success but unhappy with the way in which he was being artistically corralled, brashly replaced most synth sounds in his outfit with organics. That's when he met producer Tim Friese-Greene and started handpicking session players to meticulously realize his lofty intents.

Colour of Spring (1986) was a remarkable turning point for Hollis, and served as a model for the next record, Eden, and a near total abandonment of his earlier style. Filled with experimental textures and sprinkles of small sounds that sound so big throughout, the record's punchy, gorgeous opener, "Happiness is Easy," slowly folds through pinpoint-sharp classical guitar washes into a chorus sporting a children's choir, swelling synth strings, and unbelievable emotional release. Hollis' songwriting process now intentionally channeled improvisational and loosely formed compositional ideas into tight, organic structures. These compositions were brilliantly free, but still founded on pop. He and Friese-Green turned sketches into blueprints, then allowed session musicians to contribute ideas until they had enough material to pick from. (The December 1991 issue of Record Collector notes this same technique was popular with Can and Ornette Coleman.)

Eden was formed largely using that same painstaking process, but due to the final version's microscope-like attention to the minutiae that defines the most perfect, lonely, full moments on the album, its intensity level is far greater. It's really the little bits of Hollis' work that get me--the über-micing of an egg shaker, the hint at Hollis' inhalation before his warbly, delicate vocals tiptoe into a verse. He's continued with it through his unbelievably brain-blowing 1998 self-titled solo album, released on Polydor and available on Blueprint. It features a lot of Talk Talk alumns, but is distinctly Hollis' own--he sounds solitary, effervescent. A quarter of a decade later, Hollis still searches for that which he achieves time and time again--the creation of works that epitomize what he can do at the pinnacle of his creative power at any given time. And God bless him for that.

^ go back to topthe Birmingham Post: 24th August 2005

Pop music has always had an unquenchable obsession with the fresh and new - something marginally different that could be marketed as genuinely original, or the heirs to an irrefutably successful act.

This is more prominent now than ever before - we're told that Kaiser Chiefs are the new Blur, Coldplay are the new U2, Keane are the new Coldplay, as if everything can be traced backwards on one spindly timeline.

But it's hardly a new phenomenon. Even during the 1980s new acts were being touted as 'the new Duran Duran'. Among these collectives was Londonbased quartet Talk Talk, who didn't exactly assuage comparisons with Simon Le Bon and co when they hired Colin Thurston, who had worked with Duran Duran, to produce their debut outing.

The four-piece, with songwriter Mark Hollis at the fore, are perhaps most keenly remembered for their early singles, drawing on the insouciant glamour of the New Romantic movement.

The spangly synthpop of It's My Life - popularised recently thanks to a cover version perpetrated by the Gwen Stefani-fronted combo No Doubt - remarkably fell outside of the top 40 on its initial release, later becoming a hit in 1990, by which time the music industry and Talk Talk themselves had changed irrevocably.

By the time Talk Talk made 1988's Spirit of Eden, they had moved out of the shadow of their contemporaries - all hair spray, shoulder pads and dodgy synthesisers - to tread an altogether more singular path. Focusing on slow-building, intense yet airy chamber rock, Spirit of Eden is best described as a collection of compositions, sparse and spacious, than an album of conventional pop songs.

Adorned with glacial organ washes and almost neo-classical textures, it reveals elegant arrangements and eerily evocative timbres; the kind which have obviously influenced Doves, Elbow and Sigur Ros, while the visceral jazz-rock of opener The Rainbow must surely have been a touchstone for Jason Pierce when creating Spiritualized's heartbreak-andheroin opus, Ladies and Gentlemen We Are Floating in Space.

Even the concept of the traditional rock line-up is subverted on a record of such hushed beauty. Built upon layers of piano, organ, bass and guitar, it nevertheless takes in bassoon, oboe and clarinet, while I Believe in You features the Chelmsford Cathedral choir. Listening to its six tracks now, Spirit of Eden is still markedly alien-sounding; a feat which Radiohead have clearly tried to emulate, while coming nowhere near the spectral grace imagined by Mark Hollis.

While the Cocteau Twins and various other 4AD bands have been roundly praised for their dream-pop collages, Talk Talk's contribution to the British rock canon has long been ignored. Interestingly, the organic, autumnal atmosphere of Spirit of Eden can be spotted in the work of leading avant-rock musicians.

Certainly, their combination of jazz, classical, rock and the spacey echoes of dub, using silence almost as an instrument in its own right, lends itself to the vernacular of post-rock, and there can be little argument that Tortoise and their Chicago-based compatriots would hardly sound the same were it not for the staggering achievements of Hollis and Tim Friese-Green, presented on this near-faultless record.

Like Brian Eno's experiments with ambient pop melded with a rich sense of melody, Spirit of Eden is minimal, left-field rock at its finest; a peculiar record which rarely reaches more than a whisper, but its occasional crescendos serve as moments that accentuate the sense of quiet calm.

Spirit of Eden is an otherworldly masterpiece - icy yet inviting, unsettling but oddly compelling, not least on the closing track. The enchanting Wealth, resonating with all the gentle warmth of a lullaby, adds to the cohesive, consistent mood. As it drifts slowly out of earshot, it's almost impossible to tell when it has actually finished.

In confronting one of the clich»s of rock, namely the desire for artistic freedom, Talk Talk found themselves isolated from their peers, and dropped by their record label EMI for daring to produce something so uncommercial. The disparate themes and sounds which form Spirit of Eden were taken even further on its follow-up, 1991's impressive Laughing Stock, although it didn't quite match the heights scaled by its predecessor.

After the commercial failure of Laughing Stock, Talk Talk split, although some band members have continued to release music. Hollis' solitary solo album to date, belatedly released in 1998, has received huge critical acclaim despite incredibly modest sales. Bassist Paul Webb, recording as Rustin Man, has since collaborated with Portishead torch singer Beth Gibbons - rather appropriate, given that her group have recalled the exquisite melodies of Talk Talk's most accomplished production.

Listening to Spirit of Eden remains a limitless pleasure - it won't have you singing along in front of the mirror, but instead stands as a hugely enriching record, which has aged far better than the efforts of any of their peers.

^ go back to topMojo: January 2006

In July 1994 we were on one of those Guinness-fuelled tours of Ireland in an old Mercedes van. I’d just played at the Warwick Hotel, Galway, and on our way back to Dublin, we stopped at this brilliant old pub, Morrissey’s, in Abbeyleix. They sell Corn Flakes and groceries behind the bar, and farmers roll up in horse-drawn carts. After a few beers we set off again and my mate Donal Dineen played me Spirit of Eden in the van, and this astonishing harmonica sound just blew me away. I realised I’d completely missed the point of this album and I’d have to go back and listen properly. It came out in 1988 when I was 16, but I didn’t buy it until I was 20, living in Liverpool on the dole. Even then I hadn’t really got into it.

Most of the albums I love, like Astral Weeks or Nebraska, are performance records, but Spirit of Eden took endless hours of editing, layering of sounds, to create this astonishing soundscape.

Mark Hollis doesn’t have an instant voice, but the more I listened, I realised he was using it like an instrument, like a trumpet. I could see similarities to Miles Davis in the way they used the gaps between the notes to create this astonishing amount of space and silence. They’d thrown away notions of traditional song structure, like verse-chorus-verse. You could barely make out what Mark Hollis was singing half the time, but what comes across is that the mood of the music is darkened by some dark, personal experience he must have been through.

Everyone else at the time was using lots of processing and electronics, but they achieved all their effects by the way they miked up the recording space, so all the echoes and reverberations are natural. I’ve never heard better sounds than that screaming harmonica and the distorted guitars.

On the track Inheritance, a boys’ choir sings this beautifully uplifting melody – it gives me shivers to think of it. It came to mean even more to me when my father died a few years later because, just as the choir starts Hollis half-whispers the word ‘spirit’ and you can sense a spirit, almost as if a ghost is appearing out of the music. Spirit of Eden definitely affected how I did my new album. I actually asked Tim Friese-Greene of Talk Talk to produce it, but he couldn’t. I haven’t gone as far as they did, but I’m leaving more space in the music, Spirit of Eden was, and is, fruit for the ears.

^ go back to topThe Independent: 3rd March 2006

Talk Talk began life as the poor man’s Duran Duran – which, if you think about it, is some achievement. Yet by the time of their demise in 1991, the music being made by Mark Hollis and his collaborators was without precedent.

The success of 1986’s superior pop-rock effort, The Colour of Spring, meant the band had a free hand recording the follow-up. Spirit of Eden (1988) was the result and it left the record company aghast. This was outer-limits stuff: white-boy blues haunted by the spirits of Olivier Messiaen and Miles Davis. It was music of enormous power and dynamic range, hushed soundscapes giving way to guitars that Suede’s Bernard Butler has likened to “doors crashing open”.

Laughing Stock (1991) began where Eden left off, months of improvisation resulting in a rawer, even more diffuse opus that flitted between rock, jazz and classical. It was hard to imagine how such music, veering from the maelstrom of “Ascension Day” to the beatific “New Grass”, could be taken any further, and it was seven years before Hollis was heard from again.

His eponymous solo record was smaller in scale and wholly acoustic. Very beautiful and very quiet, this was the musician’s final word; according to his former manager, Hollis has now “retired from active duty”. (James Finn)

The Michigan Daily: 25th October 2006

True story: An English rock band establishes itself as a pop icon by releasing a series of international hits and garnering worldwide acclaim. Suddenly, the band decides it's bored with pop altogether - it releases records filled with minimalism, improvisation and experimentalism. What appears to be commercial suicide only solidifies the group's place as forerunners of (albeit loosely titled) post-rock genre. Any guesses?

Thanks to Gwen Stefani's rehashing of 1984's "It's My Life," there should be little or no doubt in the mind of educated listeners that Talk Talk were true masters of synth-pop.

But if we were to only remember the band's past contributions to pop music, we wouldn't be getting at half of Talk Talk's real legacy: musical innovation that has influenced almost every independent rock artist performing today. Their fifth and final artistic statement - their Pet Sounds, their Sgt. Pepper's; dare it be said, their A Love Supreme - is 1991's Laughing Stock.

Many die-hard fans suggest Laughing Stock is merely a spin-off of 1988's Spirit of Eden, an album that foreshadows a similar experimental concept, a similar array of instrumentation and even a similar album cover: a tree decorated with exotic birds. In reality, Laughing Stock crystallized the sound that Talk Talk was searching for and helped complete their artistic vision. Flawlessly.

While the album marks the group's baptism into a new realm of musical vision and pushes it beyond the Duran Durans of the day, Laughing Stock remains a six-song structure. Granted, a few of the tracks exceed the nine-minute border line, but theirs is no simple accomplishment. From the first strummed tremolo chords of "Myrrhman," a clear intention is revealed - these songs are meant to be listened to in succession.

On "Myrrhman," the soft, welcoming pluck of acoustic bass also introduces the listener to the band's exploration of unique instrumentation. Delicate strings and trumpet gradually enter the scene as lead singer Mark Hollis whispers "Place my chair at the backroom door / Help me up I can't wait anymore." The subtle and often dissonant trumpet lines echo composer Charles Ives, the forefather of minimalism. On this track and throughout the record there are several moments where the ghost of one of Ives's greatest works, The Unanswered Question, appears. The lesson is clear - Talk Talk did their homework.

The following track, "Ascension Day," begins with a deep drum and upright bass groove before baring its teeth through openly raucous distorted guitar chords. Ever heard of a guitar player named Johnny Greenwood? Yeah, this might be where he got it. And while we're alluding to rock styling, how about the Mars Volta? Mark Hollis was experimenting with a signature vocal style long before Cedric Bixler entered the scene. Even defunct, indie icons The Dismemberment Plan owe a debt to the more chaotic moments of "Ascension Day."

The fittingly titled "After the Flood" has a successive entrance that blends piano, organ, guitar and Lee Harris's grooving ride cymbal, which starts up after the musical downpour. Highlighted by suddenly gorgeous minor cadences of the warm, comforting organ lines, the track moves along steadily, like a wave receding from a beachhead. Here, even Hollis's lyrics (perhaps more muddled than usual) take a backseat to the wide sonic sound of the track.

The simplistic, occasionally tri-tonal guitar intro to "Taphead" makes for a unconventional duet between guitar and vocals. As Hollis faintly utters the phrase, "When do you know, y'know, you know you learn," it's probable that the singer's intent is to create a mood or feeling, rather than to form a proper sentence. More dissonant trumpet lines follow, which are quickly relieved by the album's seminal track: "New Grass." It's the sound of Talk Talk at its minimalist best. Not many bands can create such exquisite piano chords (although, in recent years, the group Rachel's may come damn close). Subtly bent three-note guitar voicings roll with the repetitive drumming as the vocals toy with a kind of staggering grace.

The album's final track, "Runeii," opens up like an Indian raga. With slides and a few muted strings, the electric guitar sets the modal mood for the piece. It's a precursor to Jeff Buckley's "Dream Brother," but with a much looser vibe. Just as the listener begins to get a feel for things, the song is quickly swept away.

Considering many of the religious overtones (not completely dissimilar from records like A Love Supreme) in Hollis's lyrics, references to "Christendom" and even the Apocalypse, it's no surprise that Talk Talk chooses to end their masterpiece in such a sudden and graceful manner.

Quite possibly, Laughing Stock personified all that the band had set out to accomplish, it marked the natural end of things. What else could the band possibly have to say? And what more can be said of such an album? (Derek Barber)

^ go back to topThe Western Mail: 3rd March 2007

Way back in 1982, Talk Talk established themselves as a 'boy band' but, unlike some of the others, they had an individual sound and artistic merit.

They weren't in-your-face and full of self-importance like many who fell neatly into the New Romantic category.

We loved them because they were innovative and experimental. People in the music industry continue to agree they never really got the success they deserved.

Although they started off in the mainstream with the singles Talk Talk and The Party's Over, the band later veered off in a different direction, taking fans with them into areas of musical incandescent brilliance.

Tracks such as It's Getting Late in the Evening and Happiness is Easy from 1986 never got the popular recognition they deserved but showed how their output was to become increasingly esoteric.

Their popularity grew quietly, though, and their Natural History album sold more than one million copies worldwide in 1990.

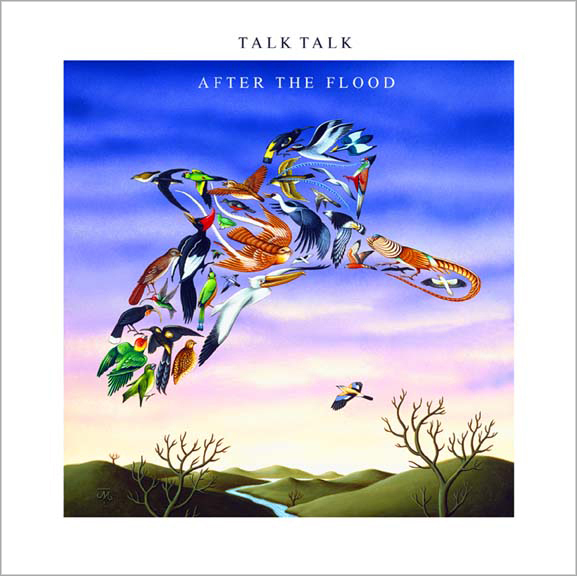

James Marsh, who illustrated Talk Talk's sleeves throughout their career, helped promote their unique style using eye-catching flying jigsaw pieces on It's My Life and a variety of Natural History Museum-style moths on The Colour of Spring.

The band's frontman, singer/writer Mark Hollis , has been described as an eccentric genius.

Born in Tottenham in 1955, he quit Sussex University and a degree course in child psychology in 1977, to return to London and concentrate on songwriting.

His older brother Ed was manager/producer of Eddie and the Hot Rods and Mark had even roadied for them before forming his own band, The Reaction.

With Ed's assistance, The Reaction secured a deal for a single I Can't Resist with Island in June 1978, which is popular with mod-revival record collectors.

After The Reaction's short-lived success, Hollis moved onto his trademark more sophisticated material. In 1981 Ed recruited drummer Lee Harris and bassist Paul Webb. With Simon Brenner on keyboards the four-piece band formed Talk Talk.

Nudged along with help from Rolling Stones producer Jimmy Miller and BBC DJ David Jensen, who offered the band a session slot on his Radio One show, Talk Talk emerged at the same time as their label mates, Duran Duran, who they supported on tour.

Incidentally, Duran Duran's producer Colin Thurston produced the album The Party's Over, that appeared in July 1982 and reached 21 shortly after their third single, Today, had reached Number 14. The LP went on to sell over a quarter of a million copies and they toured America, supporting Elvis Costello.

The fresh sound of It's My Life, with producer Tim Friese-Green, appeared as a single in 1984 but only reached a disappointing Number 46. After the single Dum Dum Girl stalled at Number 74, the group fell into releasing albums and touring in two-year cycles.

But in 1986, The Colour Of Spring finally introduced a much more expansive Talk Talk sound, with the focus moving from synthesisers to more natural instruments. The album spawned a top-20 UK hit single with the first release of the superb Life's What You Make It.

A Top 20 placing earned the band a memorable appearance on Top Of The Pops and propelled the album to number eight a month later.

Mark Hollis said he wanted to write songs that people would be listening to in 20 years' time.

The tracks, I Don't Believe In You and It's Getting Late In The Evening still make great listening - more than 20 years after they were released.

Sally Williams So who are Talk Talk?: Between 1982 and 1991 Talk Talk released a series of five increasingly esoteric albums.

They moved from an upbeat synth-drenched debut to emerge into a band with a unique sound that, by the time of Spirit of Eden, defied all genre pigeonholes to the point of being unclassifi- able.

The Sunday Times: 25th March 2007

EMI has just reissued Natural History, the very best of Talk Talk, with a bonus DVD containing the videos to their nine original chart singles.

Mark Hollis and Tim Friese-Greene's band travelled on one of the most fascinating and challenging journeys in pop history, from Duran Duran soundalikes in 1982 to experimental post-rock pioneers by the time they split in 1991.

1 Happiness Is Easy: A band on the cusp: grandeur, passion, rage, anticipating...

2 Taphead: An extraordinary collage from their final album; but looking back, too, to...

3 It's My Life: Their biggest hit; and casting a sideways glance at...

4 It's Getting Late in the Evening: One of their most beautiful, fragile songs, a B-side in 1986.

5 I Believe in You: From Spirit of Eden, the sublime album that befuddled many after The Colour of Spring.

6 After the Flood: Though it had nothing on this mesmerising track from Laughing Stock.

7 Dum Dum Girl: Still unsure where to turn in 1984, but the mixed message beguiled.

8 The Rainbow: Spirit of Eden's "What-was-that?" opening song.

9 Living in Another World: A searing, harmonica-streaked portent from The Colour of Spring.

10 Again a Game... Again: Another superb B-side, from 1984.

NonAlignmentPact.com: 24th April 2007

I came of age in the horrible, tragic nightmare of the eighties. My partner in crime for the most influential of my formative years was none other than the man himself, Mike Gunn. Everyone take out their Awkward White Doofus manuals and flip straight to the High School chapter, in case you are unfamiliar with our particularly pathological fauna. Being like I was back then — which is to say, painfully shy, gawky, lonely, and bored stupid — didn’t do much to help my inability to comfortably assimilate into suburban Houston teen life. In fact, on the contrary, Texas holds the dubious honor of being the place in which I found out just how mean kids were capable of being.

I spent five years living in a northwest Houston suburb called Jersey Village before my parents finally made their mutual hatred for one another official, and my mother moved the rest of us way south of town to the Clear Lake area. The school I walked into in the fall of 1983 was also the school for about 3000 other kids, and it was this fact coupled with my personal foibles that made my fitting in a near impossibility. I languished in this setting for a full school year before I really made any friends. My first real friend was a guy named Reese who was a true-to-heart Texas cowboy. He had the whole get-up: the ridiculous accent, big truck, critter he raised for his Future Farmers of America class, affinity for guns, and burgeoning love for the Dead Kennedys and the Sex Pistols. I can only take credit for the last part. He was a really great guy, and for the record, I really wish I could locate him and say hello today.

In the lunchroom, Reese and I would sit around, bored, thinking up ways to be a nuisance to the people around us. Since sitting at a cool-person table was out of the question, we were relegated to the dork quadrant of the lunchroom. To amuse ourselves, we would waste lots of time and lunch money flicking boiled vegetables at those geeks that we found to be beneath us on the totem pole of dorkdom. Of course it’s all relative, since flicking veggies on your peers in eleventh grade isn’t exactly going to thrust you into the arms of popularity.

Our most frequent and most pliant target in the veg toss — was Mike Gunn.

I guess you should know that all of this happened before Mike and I actually got to know each other. That event came about through the interloping of my friend, Clinton.

Clinton and I were well versed in the joys of excessive beer drinking, but I was hell bent on as much negation as I could get my hands on, and knowing that Clinton was friends with a guy who could take care of this little desire of mine was an attractive prospect. It didn’t matter that I had, just months before, made a practice of flinging boiled carrots into Mike’s own carrot-hued mane. He probably forgot that anyway, I surmised (I was wrong).

Mike’s implement of choice at the time was a tiny green plastic bong, and once we were done smoking it I knew what would become my best friend for the foreseeable future. Dope.

In our cerebral travels, Mike and I visited many states of altered consciousness, all well known to other explorers of the inner world. And as any stoner will tell you, listening to music while being high is about as good as it gets. It was in this frame of mind that I discovered the music of Mark Hollis and his band, Talk Talk.

There were so many good reasons to do drugs with Mike over at his mom’s house. The pot was almost always free. Mike’s mom was notoriously lax in her enforcement of anything vaguely resembling discipline, not to mention the fact that she was almost never home. Mike had a killer stereo and a growing selection of good vinyl. The fridge was always stocked with stoner munchies. The Gunn’s had MTV.

MTV was a great way to burn away your baked hours. In retrospect, watching as many videos for songs we both hated was a real exercise in masochism, but at the time it was more like a slightly annoying diversion. So, nestled among the Bryan Adams, and Phil Collins, and MC Hammer, and Whitney Houston, was Peter Gabriel’s inventive and somewhat trippy videos, and the occasional Camper Van Beethoven, Sonic Youth, or other token hipsters, and that made you feel like things were getting more interesting when they really weren’t.

On top of that, there were the times when you would be watching MTV at like three in the morning, already convinced that aliens were running the earth, and that we were pawns in some sort of extraterrestrial cattle-wrangling ploy. Often during these nights, we would be somewhere in the ether, fried on acid, thinking our way through great circles of sophistic garble, thinking we were approaching the absolute, when all the while we were simply chasing our tails. At these times would come up the artifacts of the eighties that were actually worth a shit, things like the movie, Fandango, or the Coen brother’s first feature, Blood Simple, or Apocalypse Now, or the stray Talk Talk video.

When you have slipped the surly bonds of sanity, and left this world for another, there are often the slightest tendrils that tether you to reality that make the whole adventure one upon which to return to this world with a new understanding. This sort of revelation often comes to me cloaked in the guise of song.

One night, while roasting our synapses – I on one of my improvised piano excursions, and Mike no doubt lost in his dungeon master fantasies – we paused our travels to take a small sojourn into the bowels of MTV. We caught the video for the Talk Talk song Life’s What You Make It. For those who are unfamiliar with Mark Hollis, he has an incredible unique voice, and his music is as good an example as any of the very best in eighties pop. Talk Talk, while still plying the pop trade, was very much catchy, smart, melodic, mature, and slightly more formal than your average new romantic pop band. There is an unforced anthemic quality to Talk Talk that always takes them out of the dated quagmire and into a more timeless space. Life’s What You Make It revolves around a little four or five note melody played on the piano. The video for the song repeatedly shows a hand playing the piano part, and this image is still stuck in my mind these thousand years later. For the rest of that night I was the bitch of this song, which in some undoubtedly perverse way had become my guide through not just the night’s activities, but the untended overgrowth of the eighties. And though it has a certain Dr Phil ring to it, the passage “life’s what you make it. Celebrate it,” is really not a bad way to approach things.

So, several years later all I knew of Talk Talk was their greatest hits CD (buy it). On it was a decent selection of what made them so adept at writing pop songs for their era. In my opinion, it really is unmatched in its quality. Eventually I began to catch snippets of information about a little known “difficult” Talk Talk album that had come out and how no one knew about it but that it was a slice of multi-dimensional genius. I knew I had to hear it, so I eventually hunted it down online. Actually what I got was probably not the one I was looking for. That honor is saved for the album Spirit of Eden (which I have yet to inexplicably hear). What I got was Laughing Stock. Without reviewing it in too much depth I’ll just say that you need to check out the album, it’s beautiful.

I spent a growing amount of time wondering what the story was behind this wildly diverse band, and in particular, I wondered what the story was behind its main creative force, Mark Hollis.

To be honest, there isn’t a ton of pertinent information about Mark Hollis out there. There’s the usual biographical data, but there is little depth to what you can stumble across beyond the basic data. Hollis is someone who falls into my favorite category of artist: the uncompromising, exploratory outsider. Pegged (probably fairly), for his bristling façade, Mark Hollis is really a bit of an English treasure. Even when Talk Talk was at its most accessible peak, Hollis’ individuality and intelligence kept them from ever being another cookie-cutter eighties outfit. If you go back and listen to their output from their relatively brief tenure, you will hear a band that is constantly pushing against the boundaries of rock/pop, and occasionally jazz/ambient to arrive at something truly unique. Starting out, Hollis quickly displayed an adept ear for melody and catchy yet elaborate pop. This gave the band an early measure of financial success. As Talk Talk’s music began to leave the accessible and obvious behind, so did they leave behind their charting ability. This meant that in the depth fearing eighties, Talk Talk was bound to clash with their label, and that’s exactly what happened following the release of their seminal album The Colour of Spring. When Hollis brought his cohorts into the studio to record the follow-up, it took them an unexpectedly long 14 months to complete the project. To make matters worse, the label had no clue what they were about to hear, and in fact fully expected more along the lines of Colour. What they got was Spirit of Eden, an exploratory, heavily instrumental album that abandons the short termed concision of the pop song for the more fertile, but less commercial, fields of experimental rock and jazz-tinged ambient meandering. The controlled orchestrations of the past gave way to a much more organic and fluid sound. As you can imagine, EMI was not amused. In fact, the story goes that once one of the thugs at EMI heard the final mixes he actually cried. The album set in motion a legal battle that effectively ended both the classic line-up of the band and their time with their label. And while Spirit of Eden was widely loved by critics and a new, smaller contingent of fans, sales were poor.

Landing on Polydor after the legal wrangling with EMI, Hollis began work on his next release. By now, Hollis was working almost entirely with guest musicians, and the recordings were, by most accounts, a strange and strained series of events. There were reports of working in total darkness, of never actually seeing Hollis in person, of incredibly difficult demands placed on all involved, and ultimately of a generally high level of peculiarity surrounding Hollis’ behavior. Whatever the circumstances, Laughing Stock is a masterpiece and a creative breakthrough for a man who was soon to completely extricate himself from the public eye.

After the release of Laughing Stock, and following the refusal from Hollis to tour, citing the impossibility of reproducing his dense work in a live setting, Talk Talk finally made it official and called it a day. In 1998, Mark Hollis released his first and only solo album to more critical acclaim and more poor album sales. By now he had cemented his image as the impossible and crazy loner, which no doubt is a mix of truth and exaggeration. If you go back and read the available interviews, you can see for yourself how he is almost painfully, and quite deliberately, removing himself from the world around him. His bandmates tell of great difficulties getting through the idiosyncrasies of his demeanor. I would imagine that he is simply a man who decided that going with the flow was simply no longer an option, and that listening to your inner voice is sometimes the only way to go in order to preserve some measure of sanity in an otherwise totally insane world. What is known about him now is that Hollis lives at home with his wife and children, is a loving father, and is not sad about retreating from the public eye. He still plays and records music at home, but none of it will probably ever see the light of day. Clearly I am drawn to people like this. My best friends share these traits and so do I. And I think that Hollis going out in a blaze of glory is the ultimate “fuck you” to the shallow, vampiric vagaries of popular culture. And while I can certainly relate to his desire to make a quiet exit, as a fan, it is a shame to lose a talent as strong as his.

Picking up on Talk Talk in the way that I did those years back reminds me of the ways in which I tie narrative threads to the screenplay of my life. I have learned to define myself through the perception of that which I find important. While I share the common practice of paying less attention to the undesirable influences on my life, I am also a total whore for the exultation of my heroes (in my own internal, and practically private way). I use the story of guys like Hollis, or Paul Nelson, or Florain Fricke, or John Coltrane, or Werner Herzog, or Jandek, or Tom Carter, or any of a whole endless list of others to help shape where I want myself to be as a person. And while I can’t actually dream of approaching the genius of these people, they serve well as a guidepost in the murk that always lies ahead. As for the forced imposition of your standard fireman, or cop, or priest, father, and typical macho hero types, you can have them all. I’ll just stick with my own personal brand of expressive and highly emotive heroics. Life, after all, has to have some mystery and magic, and god knows there’s sometimes so little of it just lying around.

And for the record, I’m sorry for flicking peas at Mike Gunn.

^ go back to topThe Independent, Ireland: 30th May 2007

'Status Quo and the Kangaroo', an hilarious book from British pop culture writer Jon Holmes, collects some of the funniest - and wackiest - true-life stories to happen to rock's great and good. Here are some that tickled JOHN MEAGHER's fancy

Bob Dylan

A number of years ago, Bob Dylan decided to drop in on Eurythmics mainman Dave Stewart. The voice of a generation knocked on what he thought was the right door and was greeted by a kindly old lady who confirmed that Dave Stewart lived there, but had popped out and would be back soon.

The great documentarian agreed to wait and was led into the sitting rom where he sat on the sofa chatting to the lady and sipping tea.

The cosy scene was shattered when Dave Stewart arrived back an hour or so later. Largely because this was not the home of Dave Stewart the rock star, but Dave Stewart the plumber.

No doubt this Dave Stewart got the surprise of his life when he found one of his musical heroes chatting to his mother.

Keith Richards

In 1994, the Rolling Stones' never-ending World Tour wound up in Toronto. But before the band took to the stage, all hell broke loose.

Guitar god Keith Richards was furious when he discovered that the shepherd's pie specially made for him had been eaten. An inquest was held to discover the culprit, but nobody came forward. Richards insisted he would not play as a result.

Finally a compromise was reached when a top chef was summoned to the venue with the express purpose to cooking Keef's favourite meal.

Half an hour after the band were supposed to have started the gig, the pie materialised. Richards ate one mouthful, then picked up his guitar and headed to the back stage area where the rest of the band were glaring at him waiting to go on.

"I think he just did it to annoy Mick," according to one crew member.

Richey Edwards

The Manic Street Preachers guitarist went missing in 1994 and was never found. The band have never been quite the same since.

But six years before his disappearance, and in an interview with a UK music mag, the socially conscious rocker decided to make a point about Aids at the height of the epidemic's scare. And he reckoned he knew how best to do it.

Taking a razor blade and carving the letters HIV into his chest, he reckoned it would be a bloody message of awareness for "the kids".

He disappeared into his dressing room and emerged 10 minutes later with the blood soaked letters VIH.

Yes, you guessed it. He had carved the letters while looking in the mirror.

Pavarotti

The Italian tenor is on the rotund side and, whenever he plays live, he has it in his contract that he most be no further than 50 metres from a toilet at any time. He also has a penchant for a special double-size disabled portaloo to be placed behind the percussion section.

Van Morrison

The grumpy Belfast singer used to share an accountant with Bob Dylan in the 1970s. Once, when the pair happened to be in London, their money man thought it would be a nice gesture to invite them out to dinner in his favourite restaurant.

But what the accountant didn't realise is that the men weren't on speaking terms. In fact, for the duration of the meal neither spoke a single word to the other or to their host.

Eventually, Bob Dylan looked at his watch and left. When he'd gone Van Morrison leaned across the table and spoke for the first time that night: "I thought Bob was on pretty good form tonight, didn't you?"

Jimmy Webb

The writer behind such tunes as Wichita Lineman and MacArthur Park was in studio working on a solo album with Beatles maestro George Martin in 1977.

Never the most conventional of songwriters, Webb had come up with a tune about gliding. It turned out he had a love for this aeronautical activity and felt his song was incomplete without actual glider noises being added to the song's recording.

Anxious to appease him, his record company hired a 2,000-yard-long airstrip for the day and rigged it with stereo microphones every six feet. This required several tons of outside-recording equipment, including three trucks, 8,000 metres of cable, wind mufflers, a mobile studio, and a state-of-the-art glider.

The ever versatile Webb decided the man the craft himself and proceeded to glide down the length of the runway exactly as planned.

Despite the money and time spent on this spectacular sound effect, the end result was exactly like someone going "ssssshhh".

The album bombed.

Mark Hollis

English new wave synth band Talk Talk were inexplicably popular in Eastern Europe in the 1980s. But that didn't stop them getting stopped by East German custom officials and being strip-searched.

Frontman Mark Hollis was taken by officials into a clinical room where he was gruffly informed that he would be given a full body search.

Hollis was told to assume the position, and bending over, he heard the snap of rubber glove being administered to a hand.

"So," said the cold German steely voice from behind him, "you're in a pop band? There is one question I wish to know the answer to."

Hollis tensed and said he would help any way he could. The probing finger was slid in. As it reached in as far as it would go, and quite possibly as uncomfortably as could be, the customs officers asked the question he had been building up to during the whole experience.

With his finger firmly ensconced in a pop star and with no trace of emotion whatsoever he simply asked: "Do you know Peter Gabriel?"

Status Quo

The bafflingly popular Status Quo were on tour in Australia in the mid-1980s. They had recently played Live Aid and were selling millions of albums.

They were 300 miles from the nearest town when their tour bus hit a kangaroo. Unsurprisingly, the marsupial came off second best and as the band members trooped off the bus they found the 'roo lying still on the ground.

It was then that they did what any self-respecting rock band would do: they dressed the kangaroo in a denim jacket, a pair of sunglasses and a bandana and lined up with it to have their photo taken.

Startled by the flash, the only-concussed kangaroo woke up, pushed the Quo aside with its fists and bounded off into the desert. It was soon lost over the horizon, still dressed like a Status Que roadie.

The band roared laughing as the climbed back on board the bus, but their guffaws came to an abrupt halt when they realised that the bus ignition keys were in the pocket of the jacket.

^ go back to topThe Guardian: 22nd November 2007